Unheard: The reality of health inequalities for ethnic minorities.

When speaking up feels like a battle

Have you ever left a doctor’s appointment feeling unheard? Maybe your symptoms were brushed off, or you were told it was “nothing to worry about” when deep down, you knew something wasn’t right. For many ethnic minorities, this isn’t just an occasional frustration—it’s a pattern.

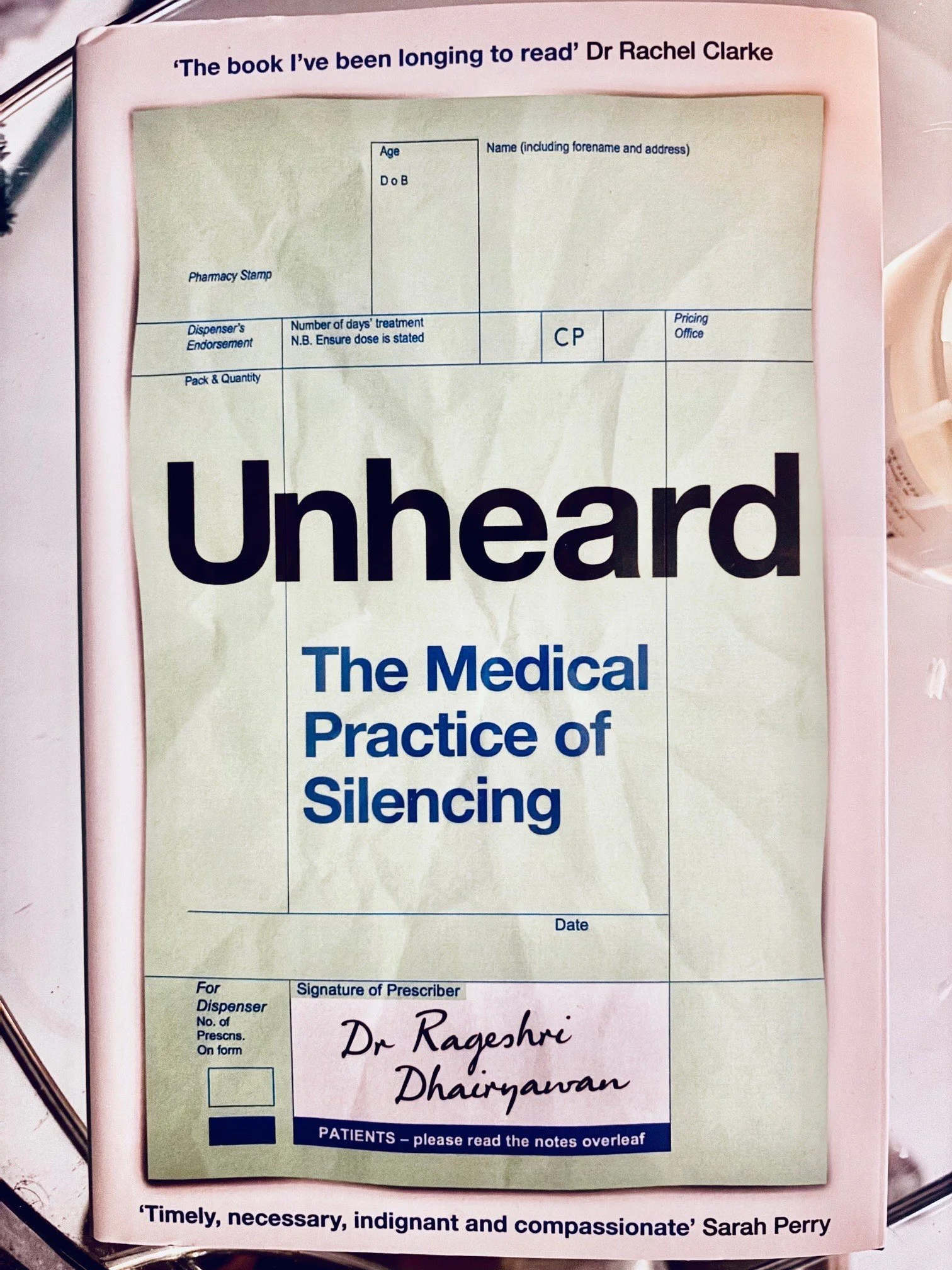

The research is clear: ethnic minorities are less likely to receive diagnoses for common conditions, and when we do, it often comes too late. Dr. Rageshri Dhairyawan’s book “Unheard” explores why this happens and, more importantly, what can do about it.

The evidence we can’t ignore

A growing body of research reveals a troubling reality: ethnic minorities often experience worse health outcomes than white populations. This isn’t speculation—studies provide clear evidence of health disparities that leave many minority groups at a disadvantage.

The Woman of the North report (2), launched in parliament 2024, exposes inequalities faced by women in the North including those of ethnic minority groups. Evidence suggests that during COVID-19, minoritised ethnic women faced significant challenges in accessing healthcare due to systemic barriers, environmental factors, and cultural differences. These women are disproportionately affected by structural and socio-economic inequalities, which impact both their physical and mental health. However, their experiences are further shaped by the combined effects of racism and misogyny, making access to appropriate care even more difficult. A study in North West England further exposed these disparities, revealing that healthcare services often failed to accommodate religious and cultural needs, resulting in inadequate and inequitable care (3). This reflects a broader pattern of systemic injustice that continues to affect health outcomes for minoritised ethnic women.

The diagnosis gap

A recent study by Cockburn & Cusworth et al. (2024) (4) examined the health records of over 13 million patients across 986 general practices in the UK to better understand these inequalities. The research found that people from Black, Asian, and Mixed ethnic backgrounds were significantly less likely to receive diagnoses for common conditions compared to the overall population across 276 different illnesses. For example:

Black individuals had a 35% lower chance of receiving a diagnosis for any given condition.

Asian individuals had a 34% lower chance of being diagnosed.

Despite a higher prevalence of diabetes among ethnic minorities, they had lower reported rates of heart attacks—suggesting widespread underdiagnosis.

These findings highlight the urgent need for healthcare systems to recognise and address the inequalities affecting millions.

Lives lost due to systemic failures

On 17th January 2025, the BBC reported on the preventable deaths of 56 babies. The statistics quoted in the article were devastating but, sadly, not surprising:

“Black mothers are nearly three times more likely to die during childbirth than white mothers (35.1 per 100,000 maternities), while Asian mothers face nearly double the risk (20.16 per 100,000 maternities), according to the latest UK figures from MBRRACE-UK.”

One particularly heart-breaking story was shared by Amarjit Kaur, whose experience reflects the realities faced by so many. Amarjit Kaur and Mandip Singh Matharoo's daughter Asees was stillborn in January 2024. We commend her bravery in speaking out, as her story echoes the struggles some of us will know too well.

How 'Unheard' explains the root cause: We are not being heard

The book 'Unheard' by Dr Rageshri Dhairyawan dives deep into why these disparities exist, pointing to one core issue, ethnic minorities are not being listened to in healthcare settings. Many people from minority backgrounds report having their symptoms ignored or downplayed by medical professionals. This leads to misdiagnosis, delayed treatment, and a growing distrust in the healthcare system.

The book also highlights how medical research and training have historically centered around white populations. This means that many healthcare providers may not fully understand how symptoms present in different ethnic groups, leading to inadequate care. The psychological impact of being repeatedly dismissed by doctors further discourages people from seeking medical help, worsening health outcomes.

What can we do while waiting for systemic change?

Fixing these inequalities will take time, but there are steps mentioned in the book that we can take to protect ourselves and advocate for better healthcare:

Before your appointment:

Plan for your consultation: write down any questions for the doctor, how you have been feeling, any changes to symptoms, medications, updates on appointments and results. This shows the medical team that you take your health seriously which in turn will help them to take your care seriously.

Let them know if you have communication needs: if you have communication needs, let the doctors know in advance. They can usually arrange for your needs, such as ensuring an interpreter is present.

Educate yourself on your condition: this can help you when communicating with doctors as you become more familiar with the terms being used. Be careful not to get overwhelmed, research to a point it is helpful not too much.

Know your rights: Learn about patient rights and complaint procedures so you can challenge inadequate care when necessary.

During your appointment:

Bring support: Taking a friend or family member to medical appointments can provide emotional support and help you advocate for yourself.

Find culturally competent doctors: If possible, seek out healthcare professionals who understand the unique health concerns of ethnic minorities.

Consider asking to see the same doctor: if you have had a good experience previously, it can be helpful for you both.

Ask who is in charge: There will always be someone who has overall responsibility for your care. Find out who this is, and if you feel you are not being heard, ask to speak to them as it is their duty to listen to you and make sure you are happy with the treatment.

Speak up and be persistent: If you feel your concerns are being ignored, don’t give up. Ask for second opinions, request specific tests, and make sure your symptoms are taken seriously. If you feel you are not being heard, explain that there is a communication problem and that they are not hearing what you are saying.

Write things down in the consultation: write down what you hear during an appointment. This can help you remember what was said and also help you during the appointment realise if you don't understand something, in which case you should ask the doctor to explain further and don't be afraid to say if you do not understand.

Ask for sources of information: ask the doctor for leaflets and recommended websites you can look at to educate yourself further.

Post and Pre appointment:

Raise awareness: Talk about these issues within your community to help others advocate for themselves and demand better care. Together we can create ‘patient activism’ where we are heard more as a collective.

Reflection: We Deserve to Be Heard

If you’ve ever felt dismissed in a medical setting, you are not alone. Too many of us walk away from appointments feeling unheard, unseen, and uncertain about our health. But here’s the truth: your health matters, and your voice deserves to be heard.

Until the system changes, we have to be our own advocates. We have to ask the tough questions, demand second opinions, and support each other in speaking up. If you know someone struggling to be heard by their doctor, share this with them. No one should have to fight to be taken seriously when it comes to their health. #TogetherWeCan

If you would like to read more:

(1) Dr Rageshri Dhairyawan (2024) Unheard, the medical practice of silencing.

(2) Bambra C, Davies H, Munford L, Taylor-Robinson D, Pickett K et al. (2024) Woman of the North. Health Equity North: Northern Health Science Alliance.

(3) Jardine J, et al. Adverse pregnancy outcomes attributable to socioeconomic and ethnic inequalities in England: a national cohort study. The Lancet 2021; 398 doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01595-6

(4) Cockburn, N., Cusworth, S., et al. (2024). Socioeconomic and ethnic inequalities in the incidence and prevalence trends of 276 chronic conditions: A cohort and cross-sectional study using primary care data between 2006 and 2021. SSRN. Available at SSRN: 4891707 or DOI: 10.2139/ssrn.4891707.

Use trusted sites when researching your condition. These include:

The Patient Advice and Liaison Service (PALS) - offers confidential advice, support and information on health-related matters.